Author: Mingming Jia

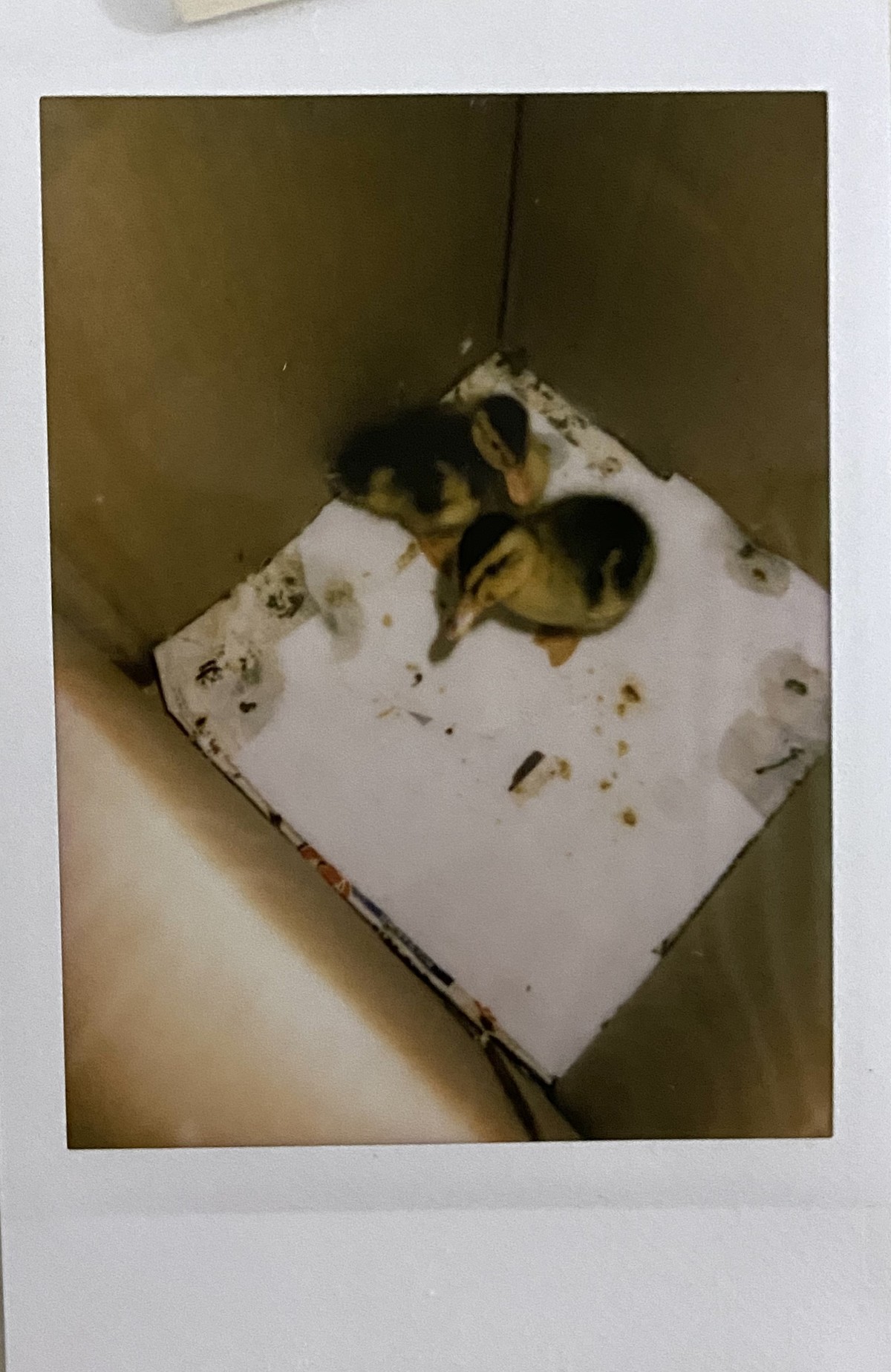

When I was nine, my parents bought me a duckling. We were visiting the countryside and I just couldn’t stop crying when I saw the little fuzzy creature. My parents eventually yielded when they realized they couldn’t bribe me with a popsicle. I guess they weren’t that happy with the notion of a duck running around in our house. But I couldn’t tell that much from the silence on our way home. I was soaked in the ecstasy of possessing a new pet.

In retrospection, though, having a duck in our house did create a rather odd image. We had delicate mahogany furniture and racks loaded with obscure books placed in a remarkably organized manner. We had a niche in the corner of our dining room where we would dedicate fruits and sweets to the Buddha. But the duck barged its way through our house, leaving plumes in every possible corner. Evenings wove the noise of my mom’s vacuum cleaner into the tantalizing smell of freshly steamed rice. Then all of a sudden the sweet scene would be torn apart by a squeaky quack. It wrecked my piano lessons—imagine Beethoven’s sonatas accompanied by the clucks of a duck.

My parents could cope with the duck’s noise, but they resented the new addition after all. At first, they simply tossed me grudging looks as the duck wobbled towards me. Somewhat later they were chasing the duck off our racks with a duster and insinuating how its presence was insanely unsanitary. Nonetheless, it wasn’t until years later that I realized it triggered something in their memories, something I, young and imperceptive, couldn’t possibly figure out.

My parents grew up as close companions in Chuansha, a remote town in suburban Shanghai. If you have seen one of those dramas where a particular character was spotlighted and the other people on stage just went dull, you would have a general idea of the circumstances of Chuansha. Chuansha was never in the limelight. It just seemed even more shadowy next to the flourishing urban Shanghai. My grandparents owned a farm there where they bred all kinds of poultries. Ducks, chickens, quails, any kind that could be sold and make a profit out of. The farm was far from a pleasant and lively place. The ground was a mixture of bird feces and dirt, releasing an unbearable odor. Dead animal bodies lay everywhere. Without a proper sanitary system, human stools were also dumped onto the ground as fertilizers.

Ducks are, therefore, foul animals that symbolize poverty. My parents could put up with living with a duck. What they couldn’t handle were the images, the scenes, and the reminiscences the duck dragged them into. Every early morning when my dad went off to school, he would see women lining up along the only river running through the place, washing their clothes while chit-chatting on random affairs. When he returned in the evenings the women had all gone, leaving the revolting water ever-flowing. The men, on the other hand, plowed shirtless beneath the burning afterglow, blurting out crude remarks. Despite the heavy imprints Chuansha left on my parents, they made it out of there and became first-generation college students.

My parents worked hard to shake off the stigmatized inferior identity imposed by their prior generation. Their accented mandarin was sneered at and their bashfulness disdained. They bought high-end furniture and stuffed themselves with abstruse knowledge to fill their insecurities, to remind themselves constantly that they no longer resemble their parents. The duck’s presence in our house just seemed so discordant, as if it shredded my parents’ endeavors.

It wasn’t long before my parents got their perfect excuse. The bird flu broke out. They consoled me the duck would have a long and joyful life before driving off to Chuansha and releasing the duck into my grandparents’ old farm. My grandparents had then relocated to a poky apartment in uptown Shanghai. My parents put a lot of work into convincing them to move.

My grandparents were humble men. Once every month they would come over for dinner and examine a new procurement of ours. A new refrigerator, an automatic flushing toilet, or maybe just an up-to-date cuisine. They would carefully avoid any obtuse questions that might expose their antiquated knowledge. Oh, the new, middle-class life their children now live.

I remember these dinners well because grandpa would always tell me something new about himself after shoving two glasses of realgar wine down his throat. He told me how he started working on that farm when he was my age; how he fed the ducks and slaughtered them afterward; how he was beaten up, hard, when he offered to go to middle school; how he was perturbed by the megapolis beyond that shanty of his, beyond Chuansha.

Now and then I seem to lose track of what it meant for my parents to leave Chuansha. My grandparents were proud of their children’s college acceptance, but they were reluctant at the same time. Having their children gone meant the farm was left understaffed, and this “abandonment” soon became a local gossip. How could they? How could they have hopped on that train to pursue a futile sheet of paper? My mom described to me how, even in her dreams, she’d see the locals chasing her relentlessly. When she dared to look back, their withering faces melted, augmented, and engulfed her. My parents eventually never returned to Chuansha during their four years of college. They took as many part-time jobs as possible during vacations, knowing the tenacity would later enable them to establish new lives outside of town.

I recall debating on the best alternative China should adopt to ameliorate rural poverty and we were all yelling numbers at each other. “30 million impoverished,” “600 thousand never made it to high school,” “4 million households live on a basic living allowance,” et cetera. We knew how to compare numbers, but then again, we knew nothing. It is harder to concern the flesh and bones and the grave conditions they reside in than to conceal them in cold statistics.

China’s current poverty relief policy consists mainly of subsidies, yet the somber prospect of intergenerational poverty reveals a concern beyond insufficient economic aid. Intergenerational poverty is chronic poverty that persists with new generations. Unlike situational poverty, which is mainly triggered by natural disasters, sudden unemployment, or acute diseases, intergenerational poverty is linked to obsolete social concepts and the absence of thorough education. The inadequate knowledge about the outside world, usually caused by geographical isolation, has impeded rural children from ever pursuing a higher ambition. Children are asked to take after the lands and their retiring parents instead of establishing themselves in major cities. Without knowing any alternative, the fear of breaking free from their present status. Also, poor educational resources determine that rural children struggle when competing with those receiving finer education. Although Shanghai imposed a relatively stricter compulsory education policy in the 1980s’, which enabled my parents to be one of the first in Chuansha to receive a college education, the reality is much grimmer for those in remoter places. Difficulty in assimilation and the guilt of leaving families behind eventually drive them home and seal them off. The phenomena repeat themselves in every generation.

Last August I visited Chuansha with my parents. They were picking up some of my grandparents’ things. I was in awe of how much the place had changed since my parents left. I saw no more shacks, only concrete houses with white paint. Dirt paths were replaced with broad asphalt roads on which cars swooshed past. No sign, not a single booklet indicated its past visage.

We found this lovely homemade restaurant for dinner. The owners, Xiao and Zhang, were a sturdy couple. They also owned a sorgo field just behind the restaurant. After serving us beautiful dishes, they told us about the betterments done by the government. Since the release of a rural construction scheme in 2018, all shacks have been removed; moors turned into orchards; households received more subsidies than ever, enough to send their children to prestigious colleges. They were confident that they would soon be well-off. When asked about their child, a twelve-year-old girl, Xiao responded with a resigned shrug. “She’s not the school type if you understand what I mean. She’ll take over the land. And c’mon, she’s pretty. She can always find herself a nice husband.”

I wandered out of the house and into the fields when they started giving impassioned speeches on the reformation. Daylight ebbed away. Among the vast field, their daughter was kneeling on the ground, both her legs stained with dirt. She was plucking weeds. As I approached she turned her face towards me. I was bewildered for a moment because I swear, she looked identical to her parents.