Author: Anyi He

Chapter 3: The Aftermath of Defeat

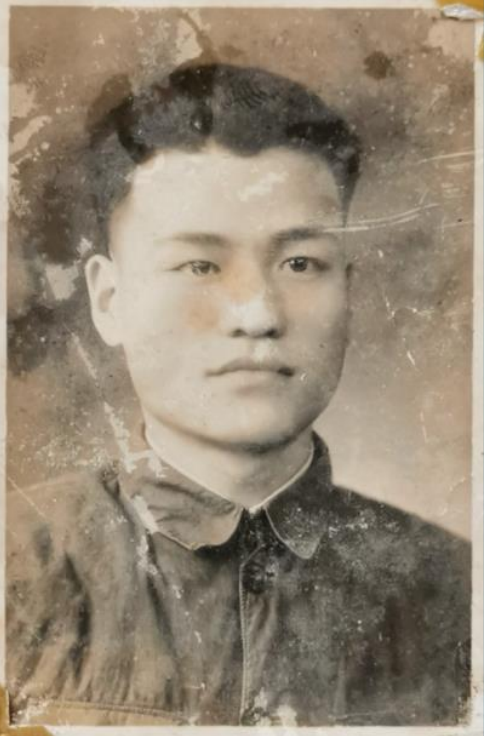

One night around 1940, Ze’an and Xiangyun took a boat from Wuhan to Wanxian Port and Wanzhou Port. They then took a sedan chair carried by two people to Changdianfang, Kaixian. This was the place where Ze’an lived in childhood. In fact, this was the place where the Tang family had resided since Tang De in the 1600s. In Changianfang, Ze’an had only 27 dan of rented land (a “dan is roughly equivalent to 100 jin of grain). What put more salt in the wound was that this land was shared with his ex-wife. After marrying Xiangyun, the land was split into three parts, and Ze’an only obtained 9 dan of rented land. Since Ze’an had a large family, the revenue from the land rent alone could not suffice the entire family's needs. Both Ze’an and Xiangyun had to take additional jobs outside to feed the family.

Since Ze’an graduated from the Whampoa Military Academy and had held military positions, the local government hired him as a mediation director. But this was not enough; he also had to open a small restaurant on the main street to supplement the family income, and Xiangyun knitted sweaters for others to earn money. At that time, no one dared to mention his affiliation with the KMT; Some of them changed names, and some of them changed their past narratives. The name Ze’an was most likely crafted around this period (some also remembered him as Ce’an from this period), hiding his past memories. The former military man who once marched in step with history’s great now found himself in a modest kitchen, far removed from the battles and politics that had defined the first half of his life.

However, his abandonment of history was only one-sided. The history that he was proud of became his eternal nightmare. The new Communist government, though initially focused on consolidating power, would soon turn its attention to rooting out the remnant of the old regime. As the 1950s progressed, Ze’an’s life was marked by a quiet resignation. He had witnessed his dreams' fall, his comrades' dissolution, and the loss of his former stature. What was left was only his family, and that was the one thing he cherished. He stayed committed to protecting the family till his death, no matter how humble the means. He and his wife lived a poor but stable life in the next ten years. It seemed that everything was over, and a new era was yet to come. The family history became dust in the corner of the history, and the future was dusty but peaceful. Ze’an didn’t regret it, and he was satisfied. Although he did not create stability for the country from his childhood dream, he managed the same with his family. Yet, he did not know that the very dream he chased in the past now became the darkest nightmare of the entire family. Not only was it a taboo that should not be mentioned, but it was also the wrath of the revolution that was only in its infancy.

Chapter 4: The Revolution’s Wrath

After 1949, the communist party established land reform, confiscating the land for the government. Luckily, though, since the main source of income for the Tang family was not from land, the Tang family earned the social classification of “small property owners” at the time, which is similar to what we now call individual business owners running a restaurant. Although the land was taken away, the social classification was better than previously thought. The social classification in post-1949 China labeled individuals and families into different social and political groups based on vague factors like economic status, occupation, loyalty to the party, and historical legacy. The classification (Chengfen) was super important under the role of the Communist Party as it determined who would be rewarded or punished. The classification also determines how resources are distributed in society, and having a classification like “landlord” could kill this person’s potential future.

Tang Ce’an’s eldest son, Tang Huaxing, was a progressive youth who had attended high school and was a member of the Communist Youth League. Influenced by the Party’s propaganda, he was faithful to the party. In his effort to join the party, Tang Huaxing severed ties with Ce’an after he graduated from the Republic of China-related Whampoa Military Academy. He saw Huaxing as a “spokesman of the evil” and never talked to him again. In 1955, he was admitted to the Department of Education at Southwest Normal University. Before his departure, he didn’t even return to Changdianfang to say goodbye to his family. At the time, Huaxing was the assistant in charge of education and culture for Wenquan District, overseeing all elementary schools in the area. (he had previously been the first principal of an elementary school in Guojia Township.) To travel from Wenquan Town to the county seat and then to the college, he had to pass through Guojia. There were no public roads then, and walking was the only available transportation method. Knowing that his eldest son, Huaxing, would go through the road, Ce’an waited on the main street for a day and a night. Ce’an knew it might be the last time he could see his first child and thus stood next to the street, staring to the end of the road without closing his eyes for a second. Yet, Huaxing did not appear.

Knowing his father wanted to see him, Huaxing purposely avoided his father when traveling to Southwest Normal University. In the university, he thought he was starting a new life, contributing to the newly born “New China,” and cutting his relationship with the past family legacies. At university, he was handsome and academically gifted, and he was admired by many. His eyes were full of future prospects, and he thought the revolution was playing his favor. Yet, history had played the deadliest joke on him.

One day, while sitting down to lunch, he noticed that his classmate hadn’t arrived yet. Feeling a bit hungry, he casually took his classmate’s steamed bun, planning to replace it with a fresh one later. A harmless gesture, or so he thought. But in the charged atmosphere of the time, where suspicion and accusation loomed over every corned, the wrath of the revolution could not tolerate this. The small act was blown wildly out of proportion. Whispers spread like wildfire. Some jealous classmates, eager to find flaws in his character, accused him of harboring “capitalist” tendencies - desiring more than his fair share to take what wasn’t his. The situation spiraled. His detractor decided to make an example out of him. They hollowed out a steamed bun, stung it on a piece of twine, and hung it around his neck like a cruel necklace, symbolizing his avarice. They paraded him through the university grounds for all to see, mocking him as greedy and selfish.

The humiliation was unbearable. Tang Huaxing, who had always stood on the top, was shattered by the merciless judgment around him, losing all his societal reputation. In his despair, he could see nothing to save him but a dark cloud in front of him. He was socially dead. He thought he had escaped the wrath of the revolution and could be part of it, but he was terribly wrong. He abandoned his family to find a solicitation, but the history convicted him in another way. He lost both his family and his future; he had nothing left. The next morning, with the weight of his torment heavy in his heart, he went to the edge of a pond, feeling completely exhausted by the injustice he had suffered. He leaped into the cold water and ended his humiliation and accusations once and for all. He committed suicide.

The other elder male in the family was Ce’an’s eldest son-in-law, Jiang Yuanguo. He graduated from Kaixian No. 1 High School in 1949 and served as the principal of Wenquan Elementary School from 1952 to 1955. In 1955, he and Huaxing both were admitted to West China Normal University. Yuanguo studied at the Department of Foreign Languages, while Huaxing studied at the Department of Education. Similar to Huaxing, Yuanguo also had the dream of reforming China. Studying in the Foreign Language department, he dreamed of aspiring high globally. However, in 1958, Tang Huaxing’s misfortune affected him. Soon after Huaxing’s death, they discovered the relationship between him and Yuanguo, and thus, Yuanguo was also labeled as a rightist. He was sentenced to three years of reeducation through labor, but in reality, he endured 20 years of confinement and surveillance. It wasn’t until 1979, the end of the Cultural Revolution, under Hu Yaobang and Deng Xiaoping's leadership that the rightist label was finally removed from his name. After the revolution, he was issued his long-overdue diploma from West China Normal University, backdated to 1959, and received a job from the government. After 20 years! He was the main reason why we could know what happened to Tang Huaxing, or else he was lost forever in the wrath of the revolution.

Ever since 1955, Ce’an has been praying for the return of Huaxing. However, in 1958, he didn’t receive any of his letters but saw the news of Huaxing’s death. Seeing his eldest kid commit suicide because of humiliation, Ce’an was destroyed. He never felt so useless, not when he was in the army, not when he was fighting the Japanese, not when he lost to the Communist Party, not when all his dreams were demolished. In 1959, the next year, Ce’an passed away in Agony.5

Chapter 5: The Women Who Endured

一年三百六十日,风刀霜剑严相逼;

明媚鲜妍能几时,一朝飘泊难寻觅。

Three hundred and three-score the year’s full tale:

From swords of frost and from the slaughtering gale

How can the lovely flowers long stay intact,

Or, once loosed, from their drifting fate draw back?

In 1960, nothing was left in the Tang family. Ce’an died in despair, Huaxing committed suicide with humiliation, and Yuanguo was sentenced to forced labor. The once large family now only has 8 members left, and most of the men are gone. The entire burden of carrying the family was left on the shoulders of the women. It wasn’t until the very end that the second son of Ce’an, Tang Jichen, started earning some revenue from a woodworking workshop.

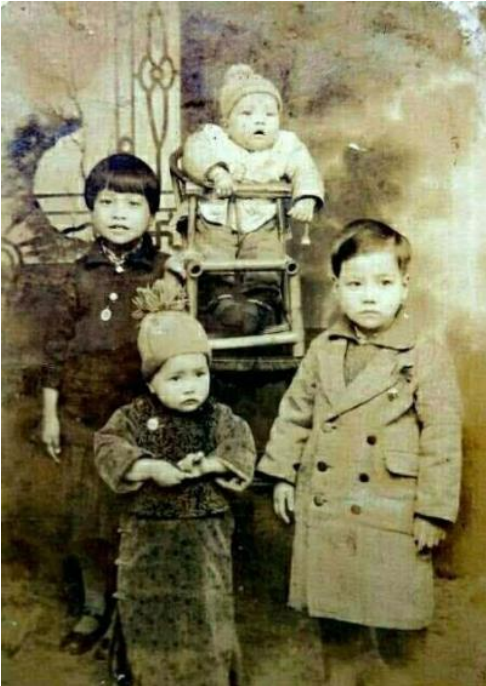

Ce’an had 7 kids, 2 boys and 5 girls: Tang Huaxing, Jichen, Junqing, Manqing, Pinqing, Zhiqing, and Jinqing. After the death of Huaxing, the heaviest burden now is on the five sisters and their mother, Xiangyun. The oldest sister, Junqing, was a primary school teacher, earning a meager salary. With her salary, the family could barely afford to buy the government-rationed food to bring back home. And then came the Great Leap Forward in 1961, the Great Leap Forward, the People’s Commune, the Communal Dining Halls, and a series of events that only deepened the family’s hunger. It became a norm in the family to eat once per day or even once per day. The future seemed dim and unending with pain. Yet the worst was still yet to come.

After 1963, the Cultural Revolution began. In 1964, during the Four Cleanups Movement, the local government, perhaps desperate to meet the quotas imported from above or perhaps based on the ROC past of the family, arbitrarily reclassified Xiangyun’s family as “landlords,” the worst kind of social classification. The government branded Xiangyun’s landlord social classification as extremely dangerous and had to be placed under government control. They took her to public humiliation. She had to stand on a stool with a sign around her neck that read “the landlord’s brat.”

Xiangyun and her three youngest daughters, Pinqing, Zhiqing, and Jinqing, were then forced out to the countryside to a production brigade named Daxing. Sleeping in the shabby hovel in the countryside, Xiangyun could feel the bitter cold that seeped through the walls, the wind howling from every corner, wrapping the room in a chill so deep that it penetrated their bones. The dissolution was unimaginable. In those dark days, Xiangyun’s spirit was crushed. Her life wasn’t supposed to be this. She often recited verses from Daiyu’s Flower

Burial Poem in Dream of the Red Chamber:

(”一年三百六十日,风刀霜剑严相逼”)

“Three hundred and three-score the year’s full tale:

From swords of frost and from the slaughtering gale”

Xiangyun grew up in a wealthy family, where servants pampered her from a young age. In her entire life, she never had to lift a finger for housework - she didn’t know how to cook, couldn’t do laundry, and lived in a world untouched by such mundane concerns. She experienced a modern life in the 19th century, from breakfast to dinner. In an era when many women still had their feet bound, she was different: not only did she not have her feet bound, but she even received a fine education. She graduated from the prestigious Hubei Women’s Normal College and read countless books as she grew up. She got to study literature and art for personal fulfillment and did not have to be concerned about the bread-and-butter issues since her childhood. Yet because of the revolution, her rich past was nothing but her burden. Like Ze’an, the past they glorified now became their worst nightmare.

In the countryside, Xiangyun had no idea how to wash clothes or prepare a meal. During those days, all her kids were busy taking care of their kids and had no time to care for their elderly mother. Left to her own devices, Xiangyun would try her hand at washing clothes, but she’d make a mess of it, sometimes scrubbing them in the bucket meant for carrying manure. Every time this happened, her daughters would exasperatedly scold her. There was a time when Xiangyun tried to cook noodles, and she dropped them into the pot before the water even came to boil, unaware of her mistake. It was a truly chaotic time.

Despite these small failings, Xiangyun had an endearing side - a childlike fondness for sweets. Growing up in a rich family, she adored treats like egg cakes, milk crisps, and peach crisps, and in the summer, she insisted on having ice creams. In those days, such delicacies were rare, sometimes even unthinkable. It was one of the few sweats that the family had at the time. Xiangyun’s grandchildren often sneak into his bedroom and carefully tuck away her unfinished egg cakes in her drawer. She often got angry, but it was the kind of anger in a normal family, between grandparents and grandchildren. It was this anger that temporarily allowed her to forget the abominable situation they were in. Every time she sees an empty drawer from where she left her deserts, she is bemused with a smile on her face, pretending to be angry at her grandchildren. In some ways, she loved the anger.

Despite the sweetness, the countryside was still unbearable for a household like Xiangyun’s, with four women barely maintaining sustenance. Facing the harsh reality that survival was impossible, they had no choice but to return to the small town where they once lived. However, without the proper household registration that entitled them to state supplied grain and oil, their monthly food rations became an insurmountable problem. One simple question was, “Where is food?” The family then was forced to purchase grain at heavily inflated prices on the burgeoning “black market.” Under communist rule, the “black market” was the secret free market that provided food for free trade. In this precarious state, Xiangyun’s family found themselves caught in the limbo of being without a rural household registration or an official urban one that could guarantee food supplies. They were known as “black households,” illegal and unprotected by the state.

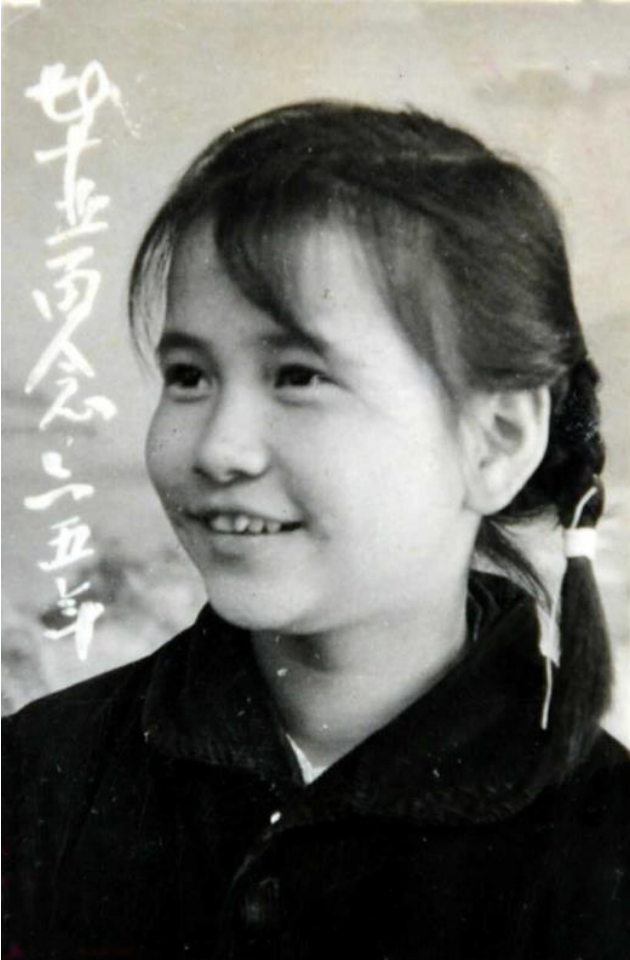

The family resorted to hope and then to education. Xiangyun’s youngest daughter, Tang Jinqing, stood out in terms of her radiant beauty and keen intelligence. At the time, at Wenquan Middle School, where she studied, she was distinguished in the class, far exceeding her peers, despite her family's many hardships. Xiangyun’s eldest son, Jichen, partially covered Jinqing’s high school expenses to support her. In addition, Junqing sent 4 yuan each month to help Xiangyun's eldest daughter despite her modest salary of 33 yuan, which was barely enough to support her family of four. Yet, that was only the school tuition.

Living together, Xiangyun, Pinqing, Zhiqing, and Jinqing battled against poverty daily. To make ends meet, Xiangyun returned to the knitting business and knitted sweaters by hand for others, earning only 3 yuan per sweater from her labor-intensive work. Even with the most meticulous effort and in the luckiest month, she could only knit about three sweaters, bringing in a meager total of 9 yuan. This was the entire family’s income. Every yuan was stretched to its limit, and every meal was a struggle.

Bearing the difficulties, the youngest kid, Jinping, did not fail the family’s expectations. After graduating from junior high, she worked hard to excel in her high school entrance exam, achieving remarkable results. With dreams of the future, she applied to college with jubilation in her heart. Yet, like all other family members, her dreams were crushed by the wrath of the revolution. “Her father had been a graduate of the prestigious Whampoa Military Academy,” read the person reading her form. Immediately, ignoring all her academic achievements, her destiny was fixed. Colleges would not accept someone once affiliated with the Nationalist army and not even mention her mother Xiangyun’s social classification as “landlord.” This rejection, rooted in politics rather than merit, became an eternal wound in Jinqing’s heart and Jinqing graduated from high school remained a source of lasting pain. Even now, she will always be deeply tormented seeing other’s graduation certificates.

Tang Jinqing, at the tender age of 15, just finished high school at a time when most young girls were full of dreams and hope for the future, found her dream vanished before she even started reaching it. To her, there was no future in education, no job prospects, and no path to a better life. This meant all the time, the money, the effort she and the family spent had vanished into the void. Instead of blossoming, Jinqing found herself thrust into the harsh reality of manual labor, which required her to burn lime - a grueling task that consumed her youth.

Burning lime was a job that not only gave birth to stones but also gave birth to Jinqing’s spirit. It began with scouring the riverbanks for the right pebbles, selecting each one by hand under the scorching sun or in the biting cold. After this came the backbreaking work of hauling the heavy stones to the kiln, which would be fired into lime. The work was still not over when the lime was made; she also had to carry the processed lime to customers, walking miles on rough, dusty roads, sometimes even without shoes. The labor was exhausting, dirty, and especially brutal under the blistering summer sun, where the heat was almost unbearable. The sweat blinded her eyes, and her skin raw from the lime’s caustic touch. It was even inhuman to the adults, not even mentioning to a 15-year-old girl. Yet, for all this effort, she would earn only 80 cents to 1 yuan a day, and if she worked from dawn to dusk for a month without rest, she might bring home around 25 yuan. For their family at the time, even this was enormous, vitally relieving the sustenance burden on the family. Holding faith that this would help the family survive the desperate times, Jinqing worked relentlessly, enduring every second she experienced.

One year, when the geological team came for recruitment, the fourth daughter, Zhiqing, was luckily selected. She had grown up with dreams of escaping the life that had been thrust upon her, a life of hardship and poverty, and now she finally had a chance to escape. When she passed the initial selection, it felt like a rare stroke of good fortune, a glimmer of light in her otherwise dim world. She didn’t believe it might be her chance - to finally break free from the oppressive limitations that had defined her life.

But again, that glimmer of hope was extinguished in an instant. As she sat in the dingy recruitment office, filling out the necessary forms, the officer’s gaze fell upon a single line: her father’s name, Tang Ce’an, and his credentials — a prestigious Whampoa Military Academy graduate. The officer’s face turned immediately from welcoming to indifferent. That name, that association, was enough. Without any hesitation, the officer took the form away from Zhiqing and closed her file. “Not eligible,” he declared, and then her application was rejected without further consideration, and the door to the future was once again slammed shut.

In those dark, stifling years, Xiangyun and her daughters - Pinqing, Zhiqing, and Jinqing - endured unimaginable uncertainty and fear. Some say, “When God closes a door, He opens a window,” but at the time for the family, god not only closed the door but called the window, the ground, the chimney, everything, locked the family in the basement. The shadows of political suspicion loomed over the family daily, and in their hearts, a silent question echoed relentlessly: “In the vast, unpredictable world, where is the path? Where is the existence of the endless struggle?”

Without any further solutions, the women resorted to their last choice: marriage. Born of desperation, the fourth daughter, Zhiqing, married an elderly worker from the Wutie factor, a man old enough to be her father. Although not a match of love or companionship, the marriage allowed her to bargain with fate. The marriage ensured that there was food on the table, and she would not go to bed with fear and hunger each night, and that was enough for her to make the decision. The third daughter, Pinqing, copied her success, found herself wed to a man who made his living as a scale maker. She, too, understood the bitter truth: in those times, marriage was less about finding a life partner and more about survival.

The youngest daughter, “Jinqing,” was in a similar plight. She was introduced to a peasant called Zhang Juchen through a matchmaker. For three generations, the Juchen family had been farmers and were classified as poor and low-middle peasants, a highly favored status then. For Jinqing, whose social classification is “landlord,” marrying into a poor peasant family was ironically considered “marrying up,” climbing the social status since she now gets to share the “peasant” social classification with her husband. Because of this marriage, the family now had a steady food supply. Juchen was part of a production team on the outskirts of Kai County, a small town surrounded by fields and farms. His team was responsible for growing vegetables for the county and feeding the townspeople with fresh produce. They were known as “vegetable farmers,” a simple title that curried significant privilege: a monthly state-supplied grain quota. This was as precious as gold in a world where food shortage was everywhere.

Jinqing as an example; she worked relentlessly in a barren and often unyielding land. She toiled from dawn until dusk, planting rows of napa cabbage, her hands raw and cracked from the cold, her back aching from hours bent over the Earth. Yet, even after all this, the cabbages sold for a mere 5 cents per Jin (0.5kg), barely enough to scrape by. The family’s income was so meager it was almost laughable, but there was nothing funny about hunger.

Jinqing, with her tiny stature, refused to give up. She had endured long enough already, and she wouldn’t stop here. In addition to farming, she took on extra work wherever she could find it. She would load a heavy handcart with honeycomb briquettes - bundles of compressed coals used for heating and cooking - and push it through the narrow, winding streets, delivering them to households in town. She often carried a cart weighing nearly 500 kilograms, more than ten times her weight, from one side of the mountain to another. She did this, day after day, week after week, for a few extra coins to buy another handful of rice or a few more vegetables. Even when every path was sealed shut, she would fight her way to the future with her bare hands and bleeding heart, carving a tunnel to freedom against all

odds.